GDPR, Data Governance, and Why “It’s Just a Log” Is Never Just a Log

From legal checkbox to architectural blueprint

First of all, let me apologise for not having been active here for a while, life happened, summer struck and time went by.

I will try to post at least once a month from now on!

Moving on, I’ve been pretty vocal lately on LinkedIn about Governance and Privacy by design in relation to GDPR and what practices are good and what are absolutely bad to have in your engineering team.

There’s a recurring scene I’ve lived through (and I bet many of you have too): someone asks for a data subject access request (DSAR), and suddenly the entire company is playing hide and seek with databases, backups, and log files. Marketing swears the data is in HubSpot. Engineering shrugs toward Postgres. Someone remembers a dusty S3 bucket with “user_logs_2018.zip.”

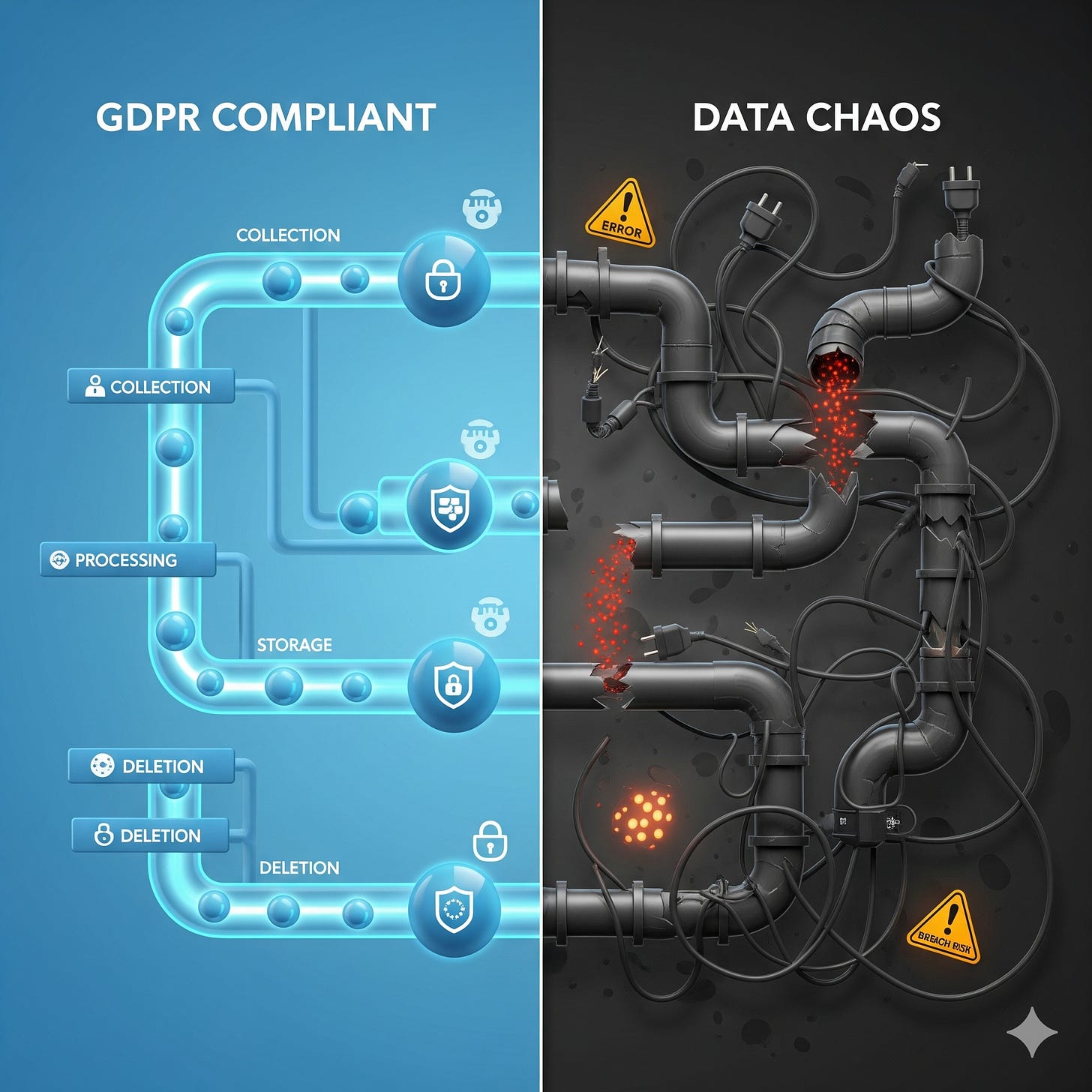

That’s not compliance. That’s chaos.

And under GDPR, chaos is expensive.

GDPR Isn’t Just Law, It’s Architecture

The GDPR gets framed as legal overhead, a box ticking exercise for the lawyers. But the truth is simpler (and scarier): it’s an architecture problem. The regulation is clear about what you can’t do: hoard personal data forever, forget about retention, or shrug off backups.

The less obvious part? GDPR pushes you to design systems differently. Privacy by design and by default isn’t a slogan, it’s Article 25 of the regulation. It means your database schemas, pipelines, and log configurations need to assume that data must one day be deleted, anonymized, or ported elsewhere.

Treating compliance as an add on is like deciding you’ll install brakes after the car’s already on the highway. You can try, but you’ll either crash or pay a fine the size of your annual revenue.

Data Governance: Boring Until It Saves You

Nobody gets excited about data governance. It’s rarely celebrated at board meetings, and if you call it a “cost center,” you won’t be wrong about how most execs see it. But it’s the only way GDPR stops being an existential risk and starts being a competitive advantage.

If you don’t know where data lives, who can touch it, or how long it stays, you don’t have governance, you have a time bomb.

And GDPR doesn’t care whether you’re Meta or a 10 person SaaS startup. You’re expected to know, to control, to prove. “We think it’s in staging” is not a compliance strategy.

The Myths We Tell Ourselves

“It’s just a log.” Nope. IP addresses, device IDs, session tokens, all personal data. Keep them forever “just in case” and you’re violating storage limitation. Legitimate interest for debugging exists, but it doesn’t give you a free pass to hoard.

“We’ll clean this up later.” Translation: “we’ll wait until a regulator or a breach forces us.” By then, “later” comes with a 4% of revenue price tag.

“We’re too small to matter.” Small businesses don’t dodge fines. They just get smaller fines more often, cookie banners misconfigured, DSARs ignored, data retained too long. Death by a thousand cuts.

Privacy by Default Means Building Differently

Here’s the cultural shift GDPR forces: instead of designing systems that can delete or anonymize data if needed, you design them so they always do, unless there’s a reason not to. Retention policies, automated deletions, anonymized logs, those aren’t edge case features. They’re defaults.

When you hear “privacy by design,” don’t picture a checkbox. Picture:

Every pipeline with a retention mechanism.

Every backup with an expiration timestamp.

Every log with anonymization baked in.

And yes, that means telling your engineers that “keep everything forever” is no longer a valid data model.

How to Actually Build Privacy by Design

It’s one thing to say “privacy should be baked in from the start.” It’s another to make that real in pipelines, schemas, and day-to-day decisions. Here are some patterns I’ve seen work (and break less often under audit):

Purpose-driven schemas. Don’t dump everything into one giant warehouse. Split by purpose (marketing, finance, support) and tie access roles directly to those purposes. In Snowflake, that looks like:

create schema marts_marketing;

grant usage on schema marts_marketing to role role_marketing_read;

grant select on all tables in schema marts_marketing to role role_marketing_read;

If you can’t answer why you’re storing something, you probably shouldn’t.

Minimize early. Don’t collect everything “just in case.” Strip or anonymize PII at ingestion—especially logs. In app pipelines, it can be as simple as masking emails before they ever land:

# Example regex for log redaction

s/[A-Z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Z0-9.-]+\.[A-Z]{2,}/[redacted]/gi

If you don’t land it, you don’t need to delete it later.

Retention as default. Data should die on schedule. Lifecycle rules in storage buckets, TTL columns in databases, and automated jobs to purge expired rows. For example, in Snowflake:

create or replace task purge_user_events

schedule = 'USING CRON 0 3 * * * Europe/Rome'

as delete from user_events where expires_at <= current_timestamp();

Deletion shouldn’t be a sprint you run before an audit.

Mask or tokenize by default. Keep analytics useful with hashed identifiers or masking policies, and reserve raw access for the rare role that truly needs it.

create masking policy mask_email as (val string) returns string ->

case

when current_role() in ('ROLE_PRIVACY') then val

else '***'

end;

alter table raw.users modify column email set masking policy mask_email;

Most queries never need the real email address anyway.

DSAR readiness. A subject index or crosswalk model that maps all identifiers back to one subject saves you from the DSAR scavenger hunt. In dbt, that might be a simple crosswalk model. If a user asks for their data, you should know exactly where to look.

Synthetic data in dev/staging. Stop pushing prod PII into lower environments. If you must sample, mask deterministically so joins still work. With dbt + Faker seeds, it’s trivial. Debugging shouldn’t require real customer data.

Compliance as Strategy

Here’s the real kicker: companies that take GDPR seriously don’t just stay out of trouble, they build trust. Users feel safer. Deals close faster when procurement sees strong governance. And ironically, systems that are compliant are usually cleaner, cheaper, and easier to maintain.

The worst fines don’t come from regulators. They come from the wasted time, the messy architectures, and the seven year old zip file nobody remembers until it lands you in the news.

So next time someone tells you GDPR is “just legal stuff,” remind them: it’s actually technical debt. And unlike other kinds of technical debt, you don’t get to decide when you’ll pay it down.

Final thought: GDPR isn’t going away. It will keep evolving, AI, biometrics, whatever comes next. The only winning move is to stop thinking of compliance as a tax, and start thinking of it as design.

Because “just a log” can end up costing a lot more than a log.